Integration of Affordable Housing and Healthcare

Author

Hayley Purdy

Cascadia Behavioral Healthcare (CBH) recently broke ground on their second project with Scott Edwards Architecture (SEA), the 71-unit Centennial Place Apartments. Located in East Portland, Centennial Place will be affordable to tenants earning between 30-60% of area median income, with a preference for families in the Centennial school district who are homeless or at risk of homelessness, and 25% of units reserved for tenants with serious and persistent mental illness.

The new project will embody one of the most fundamental lessons CBH has learned over its nearly 40-year history of serving vulnerable populations—housing is healthcare. CBH understands that providing housing is paramount to stabilizing the lives of people who have struggled with issues like mental illness, addiction, and homelessness. At the same time, housing circumstances that don’t respond to the unique challenges these residents are facing are unlikely to be successful. Housing, mental health, and physical health need to be addressed holistically by integrating housing and health.

“All the mental health treatments in the world won’t help if people don’t have a place to live where they feel secure and safe.”

VP Housing & Development, Cascadia Behavioral Healthcare

CBH and SEA: A History of Collaboration

Scott Edwards Architecture and Cascadia Behavioral Healthcare first collaborated in 2015, developing housing and healthcare facilities on a site owned by CBH in inner Portland, Oregon. CBH had operated the Garlington Clinic (named to honor the late Rev. Dr. John W. Garlington, Jr., and Mrs. Yvonne Garlington, prominent community members) on the site for over ten years before turning to SEA to help them envision how a new, expanded facility would support their mission. The goal of this development focused on delivering whole health care, with integrated mental health, addiction services, primary care, and housing on one campus to promote hope, provide access, and support the well-being of the community.

SEA believes in elevating the quality of life at home and in our communities with thoughtful planning and design—our approach considers how spaces can shape experiences. This integrated perfectly with CBH’s mission to care for the whole person through a trauma-informed, person-first approach, providing a safe and welcoming environment for everyone in our community. And so began the conversation of how to best provide an elevated, meaningful design that responds to many years of research on trauma-informed design and supports CBH’s mission to provide community-based mental health care, continued care, and patient-centered housing on a single site.

Oregon’s History of Housing/Healthcare

The integration of housing and healthcare has continued to evolve for over 40 years in the state of Oregon. In the late 1970s through the early 1980s, as mental health patients were moved from long-term residences in institutional settings to community-based care, four non-profit mental health agencies were created from what had previously been county-based services. When these new non-profits were created, each was co-located with a county public health clinic, an unusual approach at the time. Derald Walker, now CBH’s chief executive officer, was a leader with one of the agencies and recognized the benefits of connecting mental health services with primary care. At the same time, the move away from institutionalization led to a shortage of appropriate housing. The Mount Hood Community Mental Health Center, the agency Derald directed, began developing housing for people with mental illness by connecting with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The integration of housing and healthcare was unusual at this time but evolved with the support of leaders like Derald, who worked to reintegrate mental health patients into their communities by providing affordable housing.

CBH was formed when Multnomah County’s quartet of mental health service providers merged over time. Mt. Hood Community Mental Health Center and Southeast Mental Health Network merged into CBH in 2002; a year later, CBH merged with the two remaining quadrant health centers, known as Unity. In 2008, CBH brought Derald onboard and since then CBH has developed additional services, starting with support for mental health, and adding housing, addiction services, and most recently primary healthcare.

“People need more support than just a key to an apartment. Housing for vulnerable populations will fail if tenants don’t have access to services.”

Elements of Success

The components of success for SEA and CBH’s integration of housing and healthcare consist of providing tenants and the community with access to services, dynamic design, and informed design. All projects have their own successes and failures. Design continues to evolve in response to these lessons, adapting and improving how these two services are integrated into future developments. The current form of integration is not without its flaws, so we continue to call attention to these in an effort to resolve them.

Access to Services

According to Derald Walker, “People experiencing homelessness lose basic skills, if they even had them to begin with.” CBH has recognized that their most successful developments address the tenants’ most fundamental needs and provide those services within the housing development. These vulnerable populations may need not only affordable housing but also help with basic life skills: paying rent, shopping for food, cleaning their apartment, and other seemingly simple tasks. By integrating housing and health centers, we give our community members access to vital services they don’t normally have. The typical cycle for many tenants with a history of mental illness is: hospital discharge > housing > eviction > homelessness > jail > hospital. CBH understands that this cycle needs to be disrupted—eviction should be a last resort, not a first resort. The focus is on helping tenants to succeed, rather than trying to evict when problems arise.

Garlington Center

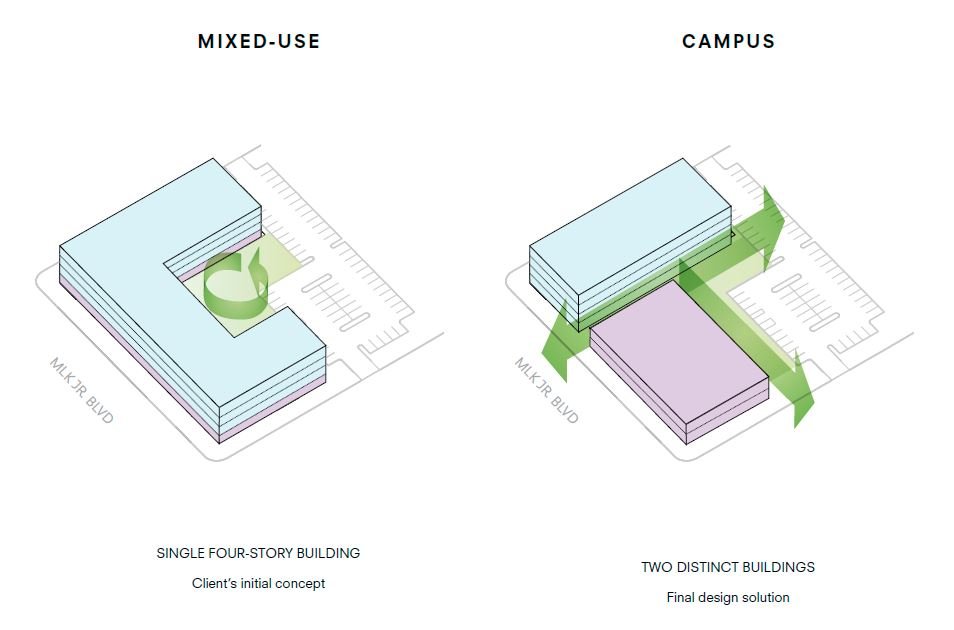

At the Garlington Center, CBH provides tenants with access to many services. The Garlington campus comprises a four-story 52-unit affordable housing building, a separate two-story health clinic with behavioral and primary care health services, and a site with space for private outdoor patios, future community gardens, outdoor gathering areas for tenants and staff, and parking for residents and clinic patients. The initial planning and concept design for the Garlington campus explored whether CBH and the community were better served with all the services being in one structure, or with healthcare and housing in separate buildings. The size and location of the site allowed SEA and CBH to consider both options, and the team eventually opted for a site with two buildings, separating housing and the clinic.

Design concepts for Garlington Center

The advantages to this strategy included locating housing on the quieter side street, reducing the height and scale of the development to feel more fitting with the residential neighborhood, providing ground floor units with semi-private patios, a neighborhood feel to the housing to create a sense of belonging and home for tenants, and a simpler, more cost-effective life-safety approach to the programmatic design of the buildings. The drawbacks to this approach included increased cost, reduced parking, and CBH electing to not maximize the development potential of their site. Yet it was agreed, the campus environment did integrate housing and healthcare through proximity and was a more considerate design for the neighborhood. This approach mirrors the holistic mission put forth by CBH, thoughtfully considering all aspects of the project and designing spaces built on a larger understanding of how the space will impact people.

CBH understood that co-locating a clinic on the site with the housing wasn’t the only access to services that their tenant population would need. The building program includes a unit for an onsite property manager who can provide support to tenants who require assistance transitioning to housing. A large community room gives space for educational and other community activities. A community kitchen in the clinic is used for classes on nutrition and healthy cooking. CBH also took the time to ensure that the staff was prepared to support the building tenants. Prior to occupying the Garlington, CBH prepared housing staff to understand and to help tenants understand that successful living takes time and patience, creating policies that allowed tenants the opportunity for improvement instead of immediate eviction.

Community room and teaching kitchen at the Garlington Center campus

The design of the Garlington Center was intended to give tenants and patients the sense that they are valued and deserve excellence, and to convey a feeling of quality and permanence to the wider community.

Access to Good Design

The collaboration between SEA and CBH has enriched the design aesthetic of CBH’s properties. Using good design to create secure, bright, and welcoming spaces in healthcare and housing is paramount to their success. CBH invested in this design-forward approach for the Garlington Campus, advocating for light and open spaces exhibiting quality and consideration. Many of CBH’s tenants and patients often feel like they do not belong in a typical setting, especially healthcare settings—it is not uncommon for patients to feel uncomfortable in these spaces and leave, never to return. Knowing this, the design of the Garlington Center intends to give tenants and patients the sense that they are valued and deserve excellence and to convey a feeling of quality and permanence to the wider community.

Trauma-informed design elements and access to social and private spaces

Access to Informed Design

At the Garlington Campus, the design was influenced by informed design processes like trauma-informed design and mental health design. SEA acknowledged in the design process how the physical environment affects all individuals, and particularly CBH’s vulnerable populations. The design of trauma-informed environments has many similarities to any good, considered design, promoting physical, mental, and social health. But in addition, these environments allow for social connection, community building, and participation. According to the National Center for Behavioral Health, trauma-informed spaces should be predictable, consistent, and allow for personal control. Other aspects of trauma-informed design that were implemented in the Garlington Center include natural lighting, access to green spaces, color schemes that emphasize cool-toned colors, clear and consistent signage, neat and clean spaces, and a balance of social and private spaces. Affordable housing by default must meet building code and accessibility requirements, but trauma-informed design and the underlying principles of universal design can further promote empowerment and reduce barriers for tenants. This additional layer of design consideration improves tenant engagement and accessibility, furthering the likelihood of success in integrating healthcare and housing.

Calming clinic lobby with signage, artwork, and green spaces

CBH and SEA also worked to create cultural relevance on the site, another component of trauma-informed design. Consideration was given to materials, language, and artwork that responds to the cultural needs of the tenants. CBH recognized that a significant population at the Garlington would be residents previously displaced from the community by urban renewal and gentrification. Therefore, an art committee was formed to select and install works by regional artists. These include a 40-foot-long dynamic celebratory mural by Arvie Smith that honors the diversity and history of the local neighborhoods of Portland. Additional works of art are focused on support and caring, tranquility and balance, the beauty of nature, social justice and civil rights, and celebrating gratitude for the community of supporters, and commemorating the Reverend Garlington. The pieces purposely reflect the Garlington Center’s mission and neighborhood history, to create connections between tenants, clients, staff, and the community.

Arvie Smith’s “Albina My Albina” Mural and Hilary Pfeifer’s “Community Giving Tree” on the Garlington Center campus

Recognizing Challenges

The integration of housing and healthcare continues to have challenges. CBH strove to provide a campus that responds to mental and behavioral health needs by locating their health clinic on the same site as housing. Yet funding guidelines limit preferences to 25% or less of the units to individuals with a documented mental illness in new affordable housing developments. Therefore, the proximity of CBH’s clinic to housing and behavioral health support services may not have as great of an impact on the majority of CBH’s tenant population as it otherwise might. As a result, CBH and SEA looked for other opportunities within the clinic to facilitate activity-based interactions between the housing tenants and the clinic’s patients and staff, with large community rooms and group rooms that host community events, gardening classes, and vaccination events.

Inherently it seems, affordable housing projects are always burdened with challenges related to cost and funding. The development of these projects nearly always involves a value engineering process, to keep the design aligned with the budget. The team agreed that it was important not to “value-engineer” out of the project materials and finishes that reduce long-term maintenance costs and ensure tenants a quality space. At the same time, SEA encouraged CBH to design and envision elements of the Garlington Campus that could be constructed and implemented with future funds or grants. A community garden, neighborhood art gallery, and additional exterior murals and artwork were planned for, with the necessary infrastructure in place for CBH to execute these components at a future date.

Integrating Housing and Healthcare into the Future

Our understanding of approaches to integrating affordable housing and healthcare continues to evolve. For Cascadia Behavioral Healthcare, the future includes working with other affordable housing developers as a service provider, bringing clinical and supportive services, or providing property management, with the goal to increase access to affordable housing for the population CBH serves. SEA has engaged with many organizations over the years that have sought to combine housing and healthcare. The design and programmatic approach vary somewhat from client to client, as each explores different strategies unique to their needs, competencies, and the populations they serve. It takes time and dedication to track the lessons learned from differing approaches, but it is critical that these lessons inform future affordable housing developments. For developers and architects alike, understanding the supportive services that vulnerable tenant populations need, and the design strategies that can sustain those programmatic goals, are vital to a successful development. It is the responsibility of those that take on these challenges to design with the strategies of access to services, good design, and informed design as central to their approach. Recognizing that housing is a form of healthcare can transform the lives of tenants, and SEA’s alignment with this understanding ensures that our solutions address the truest needs of these communities.

Learn more about Garlington Center on Cascadia Behavioral Healthcare’s website at: https://cascadiabhc.org/about/garlington/